Maurice Utrillo and his Rue Saint-Vincent

Rue Saint-Vincent that Utrillo brushed on a coarse wrapping canvas with such impasto that it would stand without the help of any stretcher. He himself, I would bet, would not have done the same then. A pale wall, decrepit and covered with inscriptions, the blackened boards of a palisade and, springing above them, in a kind of bubbling, dark foliage constitute in themselves the whole of this picture. No sky. We guess that this work, this masterpiece, was more smeared than painted, in a few hours, in a moment of terrible, torturing lucidity. But the impression that we retain is not about to die out. T

his violence, this mastery of execution, this almost unusual fury of relentlessness against the shame and the disgust he has for him make this strange canvas one of Utrillo's most overwhelming successes. There is exorcism in this vomiting. It is the confession that did not pass and which, tragically, escaped from the lips which tried to retain it. I do not know under what circumstances the unfortunate painted this canvas. We can nevertheless suppose that he was not on an empty stomach when he performed it and that, in horror at himself or disgust at having fallen so low, he wanted to free himself from his vice before leaving. succumb to it.

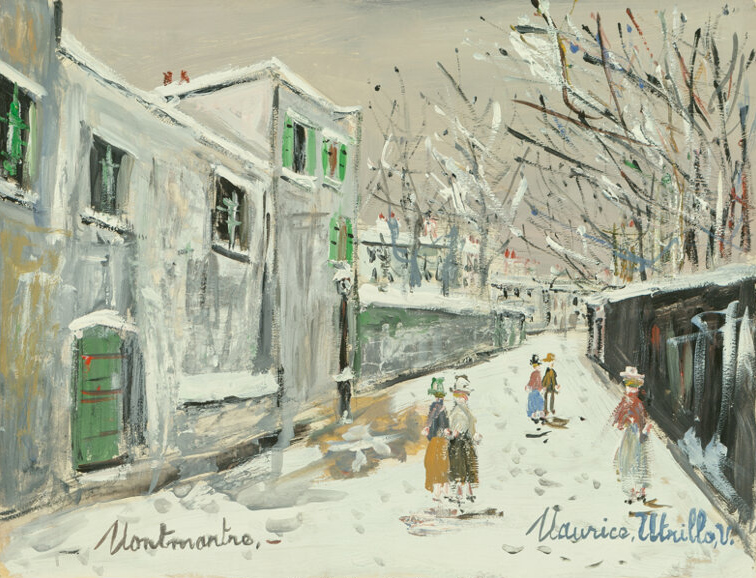

A second canvas which represents passers-by on the snow of a vacant lot, where their silhouettes take on the form of apparitions, has always made me think that Utrillo, by choosing such subjects, experienced a morose or flamboyant delight in merge with them. Here, the "vision" suggests those "paradises of sadness" that in the aftermath of his excesses in London, Rimbaud likes to evoke. The abuse of alcohol or narcotics is often the cause, but it is mixed in with the painter like an anguish in the stupor that the poet does not experience.

Where are these people going through this snow? To what dark stunner or what sanatorium? Although less striking than the other in its style, this work is nonetheless imbued with distress, with lamentable desolation. We discover, in the presence of the characters, Utrillo's obsession with feeling at certain times abandoned by the whole world. Indeed, neither the fat girl with the apron of the women of Les Halles, nor the puny man with a hunched back, nor the redhead in a mourning dress seem to be moved by supplication only by painting them the unfortunate their address. In vain he follows them in the snow where they sink, none of them turns around or pretends to stop to give the artist the time or the strength to join them.

Under the Chapelle metro station

Near garnis at twenty-five sous,

It's always him, that drunk man

Who beats the walls and who calls

Who knows who, who knows where.

His first landscapes included no other presence than his, everywhere dolent and active although invisible. We were secretly warned of this by the gloomy row of deserted perspectives where, as I myself felt so often in the days of my wandering youth, the dead seemed to me to be anonymous passers-by at the precise minute they turned the corner. corner of a street. What's the use of hailing them, waving at them? Too late ! Alas! it is always too late for Utrillo and whatever feverishness he subsequently had to populate his compositions with humble people, they are less living beings than obscure automatons who, even if they were capable of it, would not respond to him. not.

In Sannois, fortunately, no one had the idea of having him escape or of offering a sum of his paintings that would corrupt the staff, because Utrillo would never have recovered. He needed rest and care, after the excesses of all kinds that had brought him there. A great rest. Constant care. He made up his mind, allowed himself to be treated by Doctor Revertegat, whose house, located on the avenue Rozee, behind small gates, pleased him, and soon resumed painting. It was at last the peace he had so longed for in Montmartre and for which he yearned with all his sick nerves. He walked back and forth through the garden, sat down on a bench, and, deep in thought, promised himself once he was cured to change his life. The one whose sweetness he appreciated at Sannois was profitable to him.

She helped him to pull himself together, to penetrate his art, to balance it better immersed in his thoughts, promised himself once healed to change his life. The one whose sweetness he appreciated at Sannois was profitable to him. She helped him to pull himself together, to penetrate his art, to balance it better and, who knows, to mature it. This was apparent in his production: he worked more slowly, attached himself to nuances whose effects he had, during the recent period, neglected for the benefit of contrast and, little by little, cleaned up his palette of certain preparations which he considered useless in the task he set himself. The five colors which Valadon had imposed on him when he started out, Utrillo took them up again and, without tricking himself, approached these remarkable compositions of such a flexible and varied character.

A small dry tree, on the right slope, raises its desperate arms towards the sky and, through the gate, we see the area which two or three figures are peacefully approaching. In this painting which, at the bottom, concentrates a tiny, a marvelous landscape treated like a Renoir, Utrillo never reached, as far as I know, such intensity. This little sickly tree attached to the forts, behind the heavy gates in the foreground, it is he, Maurice, who is being held prisoner. He can't take it anymore. He writhes in pain and boredom. And over there, towards this corner of the suburbs where passers-by go, the glimpsed freedom, which is refused to him, obsesses him to cry.

Such works if the painter had to disappear and leave only a totally unknown name would be enough to earn him a resounding revenge. They are of a character that we no longer forget, of a strength, of a unique material and of a prodigious art. Because it is necessary to write it well, Utrillo such as it is with its so frequent repetitions, its negligence, its errors, its romanticism, seems to me like a painter whose mastery has not yet been estimated at its price. If he sometimes shocks us with his down to earth, he is nonetheless an artist of great breed who, by flashes, eclipses his contemporaries. You would look in vain, at his house, for the spices with which some, who are true artists, season their cooking and skilfully pass it on. He doesn't need it. Neither spices nor theories. But a man that his degradation has not diminished. And an admirable painter.